The Marietta Miracle

There has been a lot of discussion about what kind of role police should play in society. While arguments can get heated and tempers can flare, we all need to remind ourselves that virtually everyone can agree on two things. First, that the use of force by police should be a last resort. Secondly, that we want fewer serious injuries to civilians and officers during police interactions.

Given these two goals, what kind of training should police officers receive to achieve those ends?

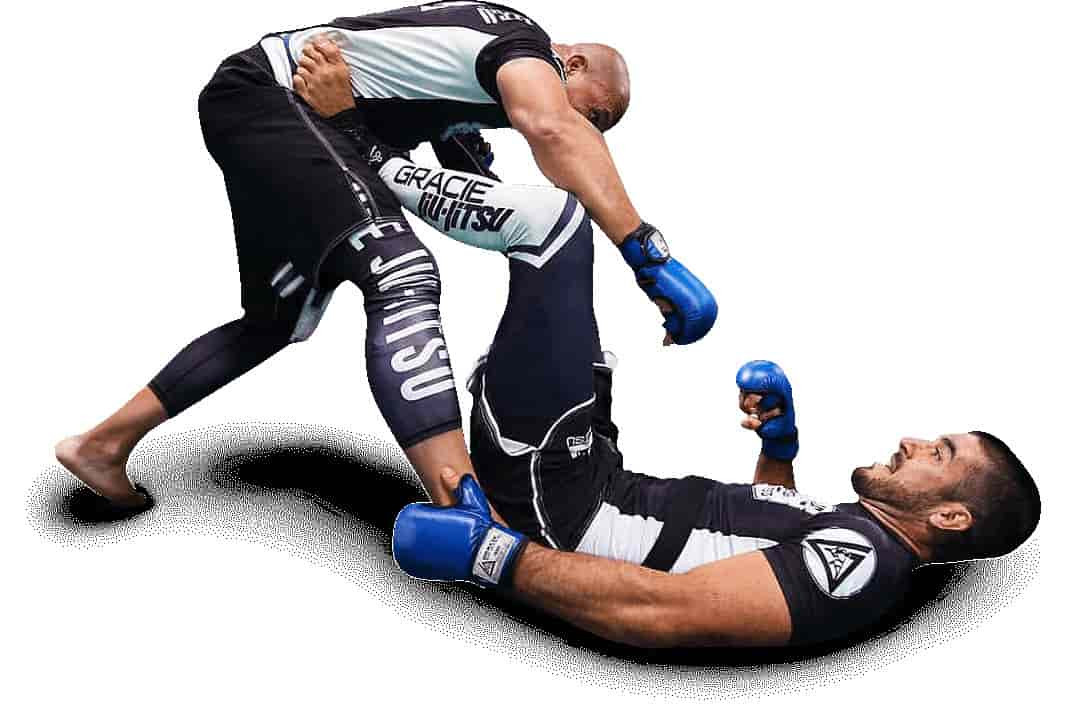

According to Rener Gracie of the Gracie Academy, one potentially answer is making jiu-jitsu a mandatory part of an officer’s training. To those who are unfamiliar with jiu-jitsu, this may sound like twisted logic. They may assume that this means police officers will just learn new ways to protect themselves and to injure civilians. After all, jiu-jitsu is a form of martial arts.

However, jiu-jitsu is distinct from other martial arts in that it places more of an emphasis on wearing down your opponent and putting them into submission holds. It also teaches discipline and trains students to remain composed even in very stressful situations. For officers, this translates into keeping their cool in a crisis scenario where a person may pose a danger to themselves or others. It means not allowing their animal instincts to override their better judgment. It means everyone walks away from the incident alive.

“I know what one hour of jiu-jitsu a week will create in a regular civilian,” Rener said in the below interview with Sam Harris. “I see it all the time, and I know that that’s the bare minimum someone needs to be sufficiently trained to get in a violent altercation and be able to just stay afloat and handle their business and not have the amygdala hijack takeover.” Rener said in reference to the part of the brain that stimulates the fight-or-flight response. “Someone will be at a place where, if they get into a fight, they’re going to be able to at least stay focused, stay calm…control the subject at the very least until help arrives.”

The Marietta Experiment

Two years ago, the police department in Marietta, Georgia, found itself in hot water after video emerged of officers punching a man at a local IHOP. The altercation, which apparently started over bacon, caused an uproar among the public and the department said that they would take steps to change.

At the time, officers in Marietta had the option of taking jiu-jitsu classes, but they were only receiving around four hours per year of training. Major Jake King could have canceled the program and said that it simply wasn’t working, but he instead took a risk by making all cadets in the police academy attend jiu-jitsu classes twice per week. These classes were held at a local, civilian-owned jiu-jitsu school that had been vetted by the department.

Five months later, the cadets graduated and described having a feeling of a confidence, which translated into more restraint out in the field. When they were put into scenarios where force was deemed necessary, they were composed and disciplined. There were no incidents of punching detainees in the head or even reports of these rookies using foul language during an altercation.

“All the things we’ve gotten used to seeing as a country don’t exist with these officers who went through the jiu-jitsu program in Marietta,” Rener said.

The Marietta Miracle

The success of the program led Major King to offer free weekly jiu-jitsu classes to all in-service officers—not just cadets or rookies. Of the 145 police officers in the force, 95 opted into this program. 50 did not. After 2,600 training sessions by the 95 officers over the last 18 months, the numbers came in earlier this year and they support Rener’s case.

In 2020, there were 33 total use of force incidents. 20 of those incidents involved the 50 officers who did not participate in jiu-jitsu training. Of those 20 incidents, 13 (65%) resulted in civilians being hospitalized. Only 13 use of force incidents were reported by the officers who participated in the jiu-jitsu program, and just four (31%) resulted in civilians being hospitalized. These numbers indicate that:

- Officers trained in jiu-jitsu were 59% less likely to be involved in use of force incidents.

- Serious injuries to suspects were 53% less likely when interacting with an officer trained in jiu-jitsu.

Additionally, the overall number of officers who have been injured while making an arrest has dropped. In the 18 months prior to program, the number of officers injured while making an arrest was 29. In the 18 months afterwards, that number dropped to 15. Even more shocking: The number of injuries in the jiu-jitsu group was 0.

Jiu-jitsu may not be a silver bullet when it comes reforming police departments, but the training does seem to make officers less likely to engage in use of force incidents, to less frequently injure civilians, and to less frequently injure themselves. “The numbers simply don’t lie,” Renner said.